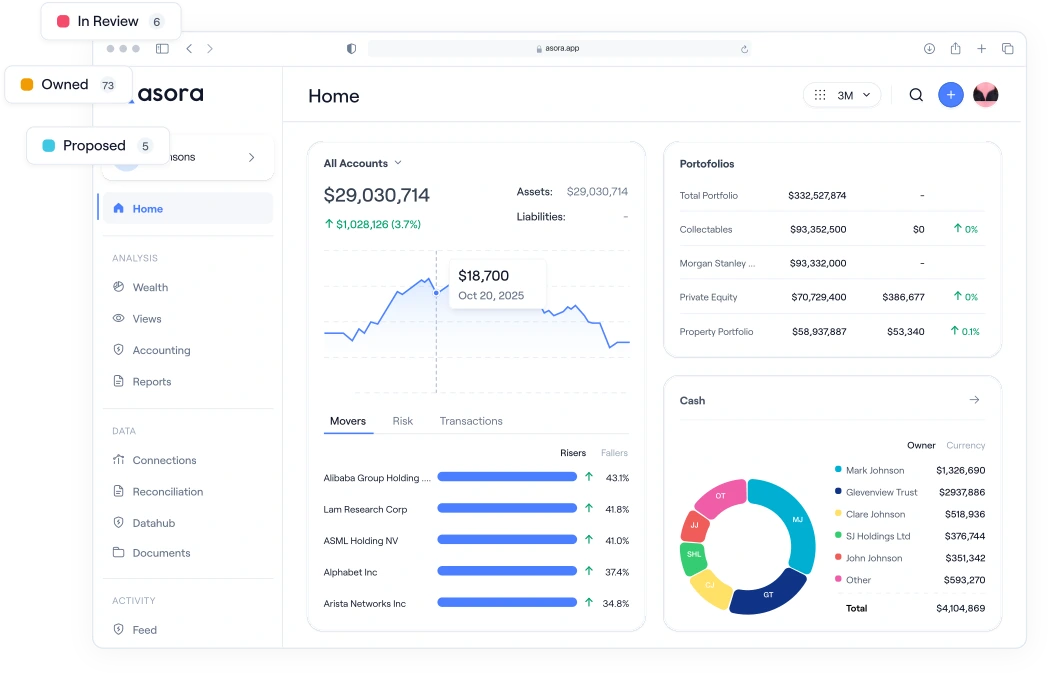

Fragmented Financial Data

We help family offices automate data aggregation, manage their assets and deliver customised reports. All in a single platform.

ISO 27001 Certified

GDPR Compliant

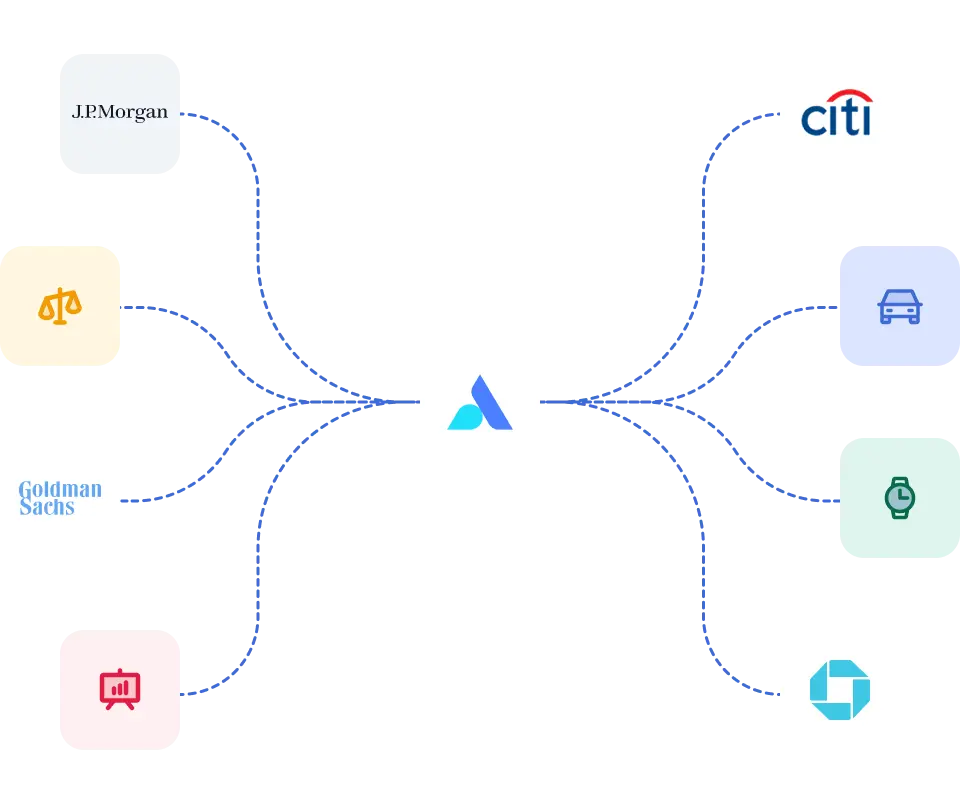

No matter what bank you use, Asora has you covered. We guarantee a connection with all banks with available data feed.

End-to-end family office management with effortless data automation and a modern UI.

Automate data aggregation, generate customised reports, and manage all assets in one place

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

100+ families worldwide trust Asora and achieve great results.

less time spent gathering and reconciling data

to create reports instead of days

to have your wealth structure live

Enterprise-grade security, purpose-built for family offices

All data encrypted in transit and at rest using industry-standard protocols.

Protect access with MFA and role-based permissions.

Proactive alerts and automated threat detection.

Host your data on a dedicated private environment for enhanced control.

Centralised visibility into user access and controls.

Independently verified to meet global information-security standards.

Asora is a family-office operating platform that centralises data aggregation, portfolio management, and reporting in one secure environment. It replaces disconnected spreadsheets, siloed systems, and manual workflows — giving you a single source of truth for all assets, entities, and accounts.

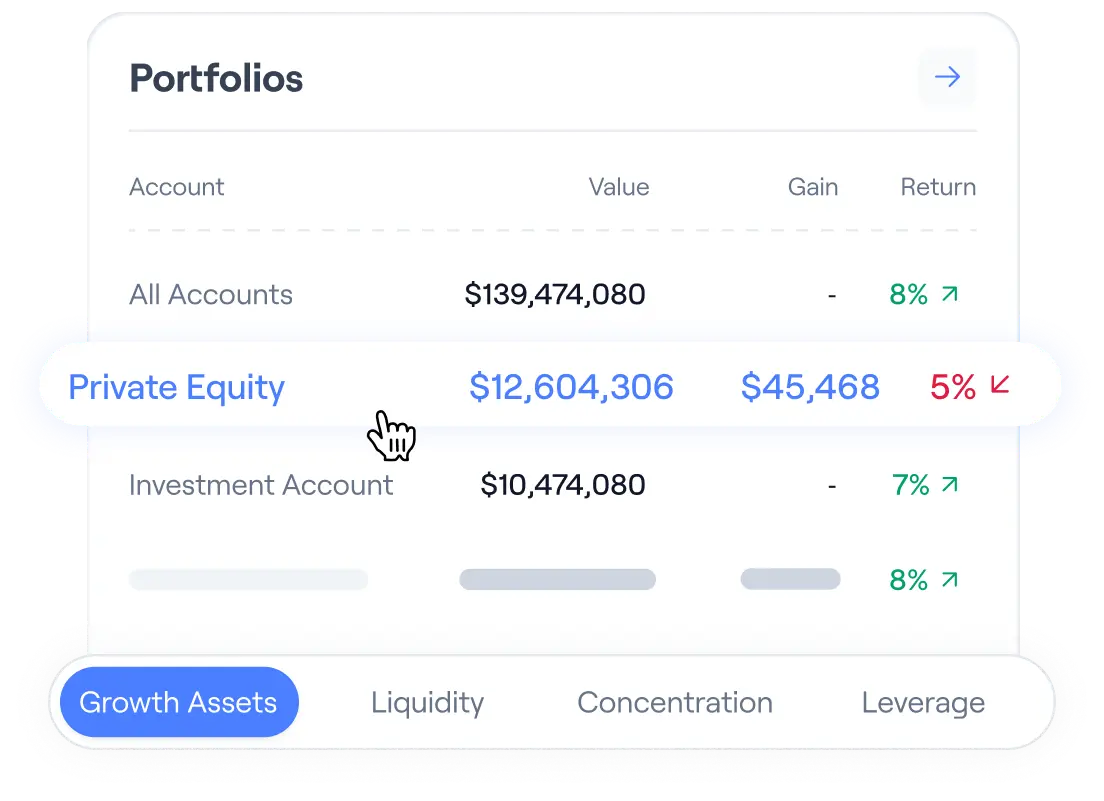

You can connect bank accounts, investment accounts, custody accounts, and track both liquid and illiquid assets — including private equity, real estate, direct investments, venture holdings, and alternative assets. Asora supports integrations with thousands of global financial institutions and uses Canoe Intelligence for private asset tracking.

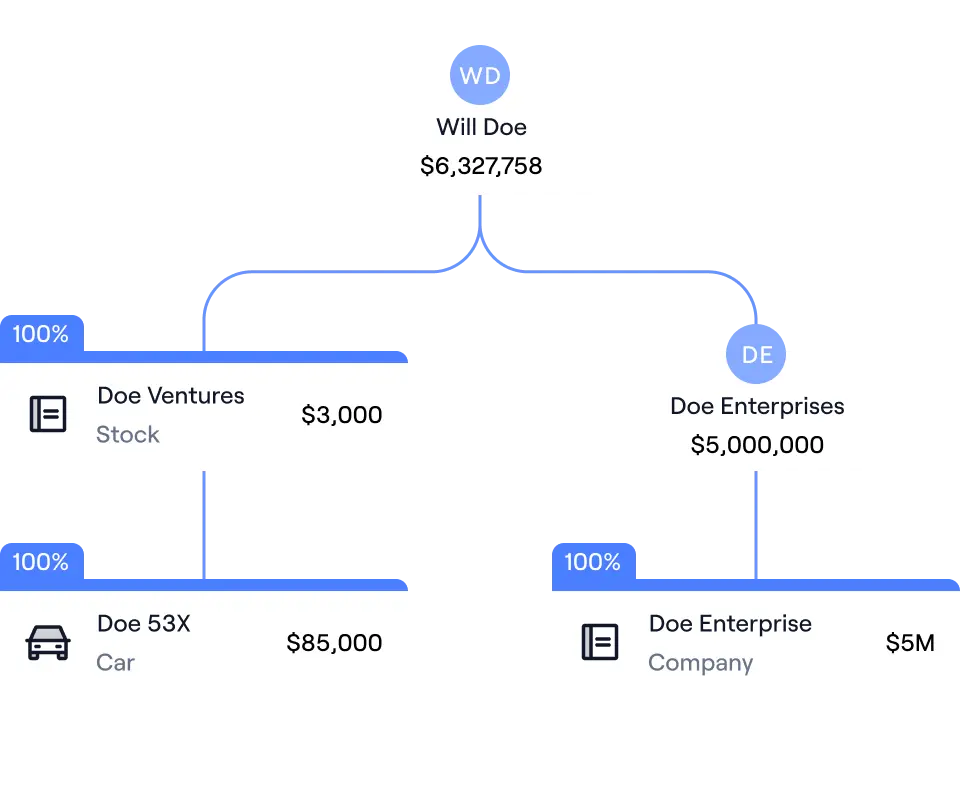

Yes. Asora supports multi-entity and multi-generation structures, trusts, companies, holding entities, and more. The platform lets you model ownership, link entities, consolidate across structures, and maintain visibility at any level — from individual holdings to consolidated portfolios.

Asora uses secure data feeds, API connections, and file ingestion from custodians, banks, and institutions to automatically import transactions, valuations, and statements. This automation removes the need for manual entry, reduces errors, and ensures data consistency across your entire portfolio.

Absolutely. Asora supports private assets and lets you track value, commitments, capital calls, distributions, and holdings. Private assets are incorporated into overall net worth and performance reports, so you get a full view of your wealth — not just liquid holdings.

Performance data is refreshed daily using close-of-business valuations for liquid assets. For private or manually tracked assets, valuations can be updated manually or via scheduled fund/custodian statements — ensuring your dashboard and reports remain current.

Yes. Asora automates data aggregation, reporting, and performance calculations across all accounts and assets. With real-time dashboards and on-demand report generation, families and offices can eliminate spreadsheet-based workflows, reduce errors, and accelerate decision-making.

Very secure. Asora is hosted on enterprise-grade cloud infrastructure, uses end-to-end encryption for data at rest and in transit, offers multi-factor authentication (MFA), and is independently certified with ISO 27001. Clients may also opt for private-cloud deployment or enhanced access controls for additional isolation.